| Citation: | Kun Li, Huimei Tian, W. Keith Moser, Steven T. Overby, L. Scott Baggett, Ruiqiang Ni, Chuanrong Li, Weixing Shen. Black locust coppice stands homogenize soil diazotrophic communities by reducing soil net nitrogen mineralization[J]. Forest Ecosystems, 2022, 9(1): 100025. DOI: 10.1016/j.fecs.2022.100025 |

| BL | Black locust |

| F | First-generation seedling plantation stand |

| S | First-regeneration coppice stand |

| T | Second-generation coppice stand |

| FR | Rhizosphere in first-generation seedling plantations |

| SR | Rhizosphere in first-generation coppice stands |

| TR | Rhizosphere in second-generation coppice stands |

| FNR | Bulk soil in first-generation seedling plantations |

| SNR | Bulk soil in first-generation coppice stands |

| TNR | Bulk soil in second-generation coppice stands |

| C | Total soil carbon |

| N | Total soil nitrogen |

| P | Total soil phosphorus |

| C/N | Ratio of soil carbon and nitrogen |

| C/P | Ratio of soil carbon and phosphorus |

| N/P | Ratio of soil nitrogen and phosphorus |

| NO3−-N | Soil nitrate |

| NH4+-N | Soil ammonium |

| AN | Soil available nitrogen |

| MBN | Microbial biomass N |

| MBC | Microbial biomass C |

| MBC/MBN | Ratio of MBC and MBN |

| Rn | Soil nitrification rate |

| Ra | Soil ammonification rate |

| Rm | Net soil N mineralization rate |

| RDA | Redundancy analysis |

| PCoA | Principal coordinate analysis |

| OTUs | Operational Taxonomic Units |

| GLMMs | Generalized Linear Mixed Models |

| BNF | biological nitrogen fixation |

Black locust (BL, Robinia pseudoacacia) is considered a promising tree species for reforestation programs due to its rapid growth rate and ability to fix nitrogen (Medina-Villar et al., 2016). Reproduction of BL plantations is primarily vegetative through root suckering and stump sprouting (Carl et al., 2019), allowing vigorous regeneration after coppicing and disturbance. Unfortunately, BL coppice plantation productivity declines after two or three harvesting rotations (Cierjacks et al., 2013; Li et al., 2021). Other adverse effects have also received widespread attention, such as soil fertility degradation, trunk bending, and limited tree height (Li et al., 2021).

BL roots are colonized with nitrogen-fixing microorganisms (diazotrophs) and thus enhance the nitrogen (N) content in soil organic fraction through N2-fixation (Cierjacks et al., 2013), which is an essential source of N to ecosystems (Reed et al., 2011). Nitrogen fixation reduces molecular nitrogen to ammonia and other nitrogen-containing compounds (Meng et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2019), mediated by bacteria and archaea that possess the enzyme nitrogenase (Reed et al., 2011; Ouyang et al., 2018). The nifH gene regulates nitrogenize synthesis by producing an enzymatic compound that catalyzes the N2-fixation to NH4+-N in the plant (Gaby and Buckley, 2011; Zhou et al., 2021). Therefore, diazotrophic abundance, diversity, and community composition have been recognized as biotic factors crucial to determining soil nitrogen-fixing capacity (Stewart et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2021). These factors have been extensively investigated, employing the nifH gene as a molecular marker (Fan et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2019a, 2019b). Generally, the rates of biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) are related to diazotrophic abundance and community composition (Hsu and Buckley, 2009; Stewart et al., 2011). The community composition, in turn, is influenced by land use, soil physical properties, nitrogen quantity, and availability (Calderoli et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2019a; Wang et al., 2021). Diazotrophs and nitrogen mineralization have a significant impact on soil nitrogen availability. Nevertheless, we still do not understand how they responded to converting BL seedling plantations to coppice stands.

Most researchers have focused on the bacteria and fungi communities, but little attention has been paid to functional genes, for instance, the nifH gene. For example, one study found that converting an Amazon rainforest to a cattle pasture altered the diazotrophic composition (Mirza et al., 2014). Another study found that forest conversion may directly or indirectly affect soil nitrogen mineralization rate by affecting soil biotic and abiotic factors such as available N (Rigby et al., 2016). Therefore, a study of the nifH gene and N mineralization can provide an insight into the influence of N dynamics on BL coppice plantations. Nitrogen is a crucial nutrient for plant and microbial growth that influences plant productivity and microbial decomposition in terrestrial ecosystems (LeBauer and Treseder, 2008). Soil N availability for plant growth is dependent on the rate of soil N mineralization, in which soil organic N is converted to inorganic N by soil microorganisms and invertebrates (Chapin III et al., 2011; Murphy et al., 2017). Such processes, including ammonification and nitrification, convert organic N (proteins, sugars, cellulose, lignin, etc.) to available inorganic forms (NH4+ and NO3−) (Fu et al., 2019). Soil N mineralization directly affects nitrification by providing substrates to nitrifying microorganisms (Petersen et al., 2012). The quantity of NH4+-N is the rate-limiting step in soil nitrification. The soil abiotic properties, such as soil pH, soil moisture, and soil depth, could describe the N mineralization rate (Urakawa et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2018; Thapa et al., 2021). At the same time, many recent studies have found that the vegetation type and microbial community also substantially affect N mineralization (Li et al., 2019). This process affects the quantity and quality of organic materials, soil biological activity, microbial community composition, and N plant-use efficiency (Rachid et al., 2013; Rahman et al., 2017; Kong et al., 2019; Yao et al., 2019). Therefore, studying vegetation types and soil properties is relevant to understanding nitrogen mineralization.

Reforestation decreases soil erosion and improves soil fertility, potentially affecting soil N fractions (Guillaume et al., 2018). Because of its effect on recovering N cycling processes, BL was used as a pioneer tree species for afforestation Mount Tai to preserve soil (Meng et al., 2020). Generally, different N requirements of specific plant species may be an underlying driver of the diazotrophic communities (Kong et al., 2019). However, the specific composition of diazotrophic communities and their associations with soil N availability under black locust coppice plantations are largely unknown, limiting our ability to evaluate the effectiveness of reforestation. Previous studies have confirmed that the conversion from seedling to coppice stands reduced soil quality and led to decreasing the relative abundance of Rhizobium in coppice plantations (Li et al., 2021). However, the impact of coppice plantation on nitrogen fixation and nitrogen mineralization is unknown. Accordingly, this study hypothesized that the coppice diazotrophic community negatively impacts soil fertility in the BL coppice plantations. Our objectives were to (1) determine the effects of conversion from seedling to coppice stands in BL plantations on the composition structure of diazotrophic community; (2) examine the effect of conversion on net N mineralization, and (3) explore the driving factors for the conversion in the diazotrophic communities.

The study site is on Mount Tai, Shandong Province, China. The mean annual temperature is 12.8 ℃, and the mean annual precipitation is 1, 124.6 mm. The existing BL stands are mostly coppice plantations, mainly distributed on south-facing slopes at elevations of 500–1, 000 m. The study was carried out in: i) a first-generation seedling plantation stand (from now on referred to as "First" or "F", 36°16′45″ N, 117°3′26″ E), ii) a first-regeneration coppice stand generated after clear-cutting of a seedling stand (referred to as "Second" or "S", 36°16′40″ N, 117°03′21″ E) and iii) a second-generation coppice stand generated after clear-cutting of a first-generation coppice stand (referred to as "Third" or "T", 36°16′40″ N, 117°3′22″ E). The principal species in the understory vegetation community are Vitex negundo, Oplismenus undulatifolius, Digitaria sanguinali, Paspalum thunbergii, Rubia cordifolia, and Oxalis corniculate. The soil type is classified as Alfisols. We sampled plants and collected rhizosphere and bulk soil samples for further analysis for each stand. Detailed information about the plots can be found in Li et al. (2021).

Three 20 m × 20 m plots were randomly selected in each seedling and coppice stand for a total of nine plots. The bulk soil and rhizosphere soil were sampled in the nine plots in August 2018. Bulk soil was sampled at 10 cm from the soil surface using a soil auger (length 50 cm, diameter 5 cm, volume 100 cm3). Rhizosphere soil samples were collected by brush (5 samples per plot). The soil samples were transported on ice to the laboratory, where they were sieved (mesh size 2 mm) and divided into two parts, one air-dried and stored at room temperature before chemical analysis, and the other stored at −80 ℃ and −4 ℃ for further analysis. In this article, FR, SR, and TR refer to the rhizosphere of F, S, and T, respectively; and FNR, SNR, and TNR refer to bulk soil of F, S, and T, respectively.

A subsample of 50 g of soil was stored at −4 ℃ and later used for the determination of microbial biomass C (MBC) and N (MBN) by the method of chloroform fumigation extraction (Margesin and Schinner, 2005). During chloroform fumigation, soil incubation in gaseous CHCl3 was extended from 24 to 48 h in our experiment to thoroughly kill all soil microorganisms (Tian et al., 2017). After chloroform fumigation, the soil samples were extracted using the solution of 0.5 mol·L−1 K2SO4. The soil extraction solution was then analyzed by Multi N/C 3100 using the high-temperature combustion method (Analytik Jena AG, Germany). The factors in the transformations from the detected soil total organic carbon and nitrogen to microbial biomass carbon and nitrogen were 0.45 and 0.54, respectively (Margesin and Schinner, 2005).

The second subsample of 10 g was air-dried and used to determine soil nitrogen mineralization rates. N mineral fractions (NH4+-N and NO3−-N) were determined using the aerobic incubation method (Hart et al., 1994). For this purpose, 10 g soil through a 2-mm sieve was adjusted to 40% of the maximum water holding capacity. Samples were incubated in a constant temperature incubator at 25 ℃, and N extractions were performed at 0 and 14 d after incubation. The NH4+-N and NO3−-N contents were extracted using 50 mL of 2 mol·L−1 KCl solution. The soil mineralization ratio was obtained by subtracting the initial (zero-day) and final (14 days) ammonium (NH4+-N) and nitrate (NO3−-N) concentrations (Hart et al., 1994). Net N mineralization rates were calculated as the changes in mineral N contents and reported in mg N dry soil per 14 d.

The third subsample of 30 g was air-dried and used to determine soil nutrient content, including total soil carbon (C), total soil nitrogen (N), soil nitrate (NO3−-N), soil ammonium (NH4+-N), and soil phosphorus (P). The C and N contents were measured by combustion in an elemental analyzer (Costech ECS4010, Italy). NO3−-N and NH4+-N were extracted by shaking 20 g of fresh soil in 100 mL of 2 mol·L−1 KCl solution for 1 h and were analyzed with a continuous flow analytical system (AA3, German). Available N (AN) was a sum of NO3−-N and NH4+-N. P content was extracted using the Olsen method and measured by a continuous flow analytical system (AA3, German).

Microbial DNA was extracted from soil samples (frozen at −80 ℃) using the E.Z.N.A.® soil DNA Kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Norcross, GA, US) according to the manufacturer's protocols. The final DNA concentration and purification were determined by NanoDrop 2000 UV–vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, USA), and DNA quality was checked by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. The primer pair PolF (5′-TGCGAYCCSAARGCBGACTC-3′) and PolR (5′-ATSGCCATCATYTCRCCGGA-3′) was used for amplifying the nifH gene. Each reaction was carried out in a 25-μL volume which included 0.5 μL of each primer (10 μmol·L−1), 2 μL DNA template (1–10 ng), 12.5 μL of Premix Taq™ (2 × ) (Takara) and 9.5 μL ddH2O. The PCR conditions were as follows: 5 min at 95 ℃, and then 35 cycles of 30 s at 95 ℃, 30 s at 58 ℃, and 45 s at 72 ℃, and a final extension at 72 ℃ for 6 min (Wang et al., 2018b). With three replicates, each sample was amplified. Then, three PCR replicates of the same sample were mixed with the same quality based on concentration and purified with AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen Biosciences, Union City, CA, USA).

Purified amplicons were pooled in equimolar and paired-end sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, USA) according to the standard protocols by Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were clustered with 97% similarity cutoff using UPARSE (version 7.1, http://drive5.com/uparse/), and chimeric sequences were identified and removed using UCHIME. The taxonomy of each nifH gene sequence was analyzed by the RDP Classifier algorithm (http://rdp.cme.msu.edu/) against the Silva (SSU123) nifH database using a confidence threshold of 70% (Gaby and Buckley, 2014).

The rates of ammonification (Ra), nitrification (Rn), and net N mineralization (Rm) during incubation were defined as the difference between initial and final NH4+-N, NO3−-N, and net mineral N (sum of NH4+-N and NO3−-N) concentrations, respectively (Kong et al., 2019):

Ra = (NH4+-Ni+1 – NH4+-Ni)/t

Rn = (NO3−-Ni+1 – NO3−-Ni)/t

Rm = Ra + Rn

where NH4+-Ni and NO3−-Ni are the concentrations of NH4+-N and NO3−-N before incubation, NH4+-Ni+1 and NO3−-Ni+1 are the concentrations of NH4+-N and NO3−-N after incubation, respectively; and t is the number of days of the incubation period.

All responses were modeled as two-way factorial designs using Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMMs) that included the main effects of soil, generation, and soil × generation interaction. A random heteroscedasticity component for each soil × generation combination was also included for all models. Each model utilized the appropriate conditional distribution of the response based on the response range. Specifically, C/N, C/P, MBC, MBC/BN, MBN, N/P, NH4+-N, and NO3−-N were modeled as Gamma with a log link, Ra, Rm, and Rn were modeled as Gaussian with an identity link, and C, N, P were modeled as Beta with a logit link. In addition, we computed Hill Numbers analogous to Shannon's Diversity Index (q = 1) for each treatment combination (Hill, 1973; Chao et al., 2014). The responses are thus defined as effective species counts and modeled as a Poisson distribution with a log link.

All model prediction confidence bounds were controlled for family-wise experiment rates using the Sidak adjustment method with α = 0.05 (Westfall and Young, 1993). In addition, multiple comparisons were adjusted for family-wise experiment rates using Tukey's HSD method, with α = 0.05 (Kramer, 1956). Data were analyzed using the R statistical environment version 4.0.5 (R Core Team, 2021) using R packages glmmTMB (Brooks et al., 2017) and emmeans (Lenth, 2021).

To illustrate the clustering of different samples and to further determine the microbial community structure, Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA), Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) based on Bray-Curtis distance were used to analyze the diazotrophic communities at the genus level. Redundancy analysis (RDA), Random Forest, and Mantel tests were used to link the variation within the microbial community, functional structure, and soil properties to environmental variables. Spearman correlation analysis examined the relationships between the abundance of the nifH gene, soil nutrients, and net N mineralization. PCoA, RDA, PERMANOVA, Mantel tests were conducted using the vegan package with R software. Random Forest analysis was conducted using the randomForest package with R software. Circos plot was created with the Circo-0.67-7 software (http://circos.ca/). Data analysis and graphing were performed with SPSS version 26.0 statistical software (SPSS, Chicago, USA) and R software (version 3.6.1).

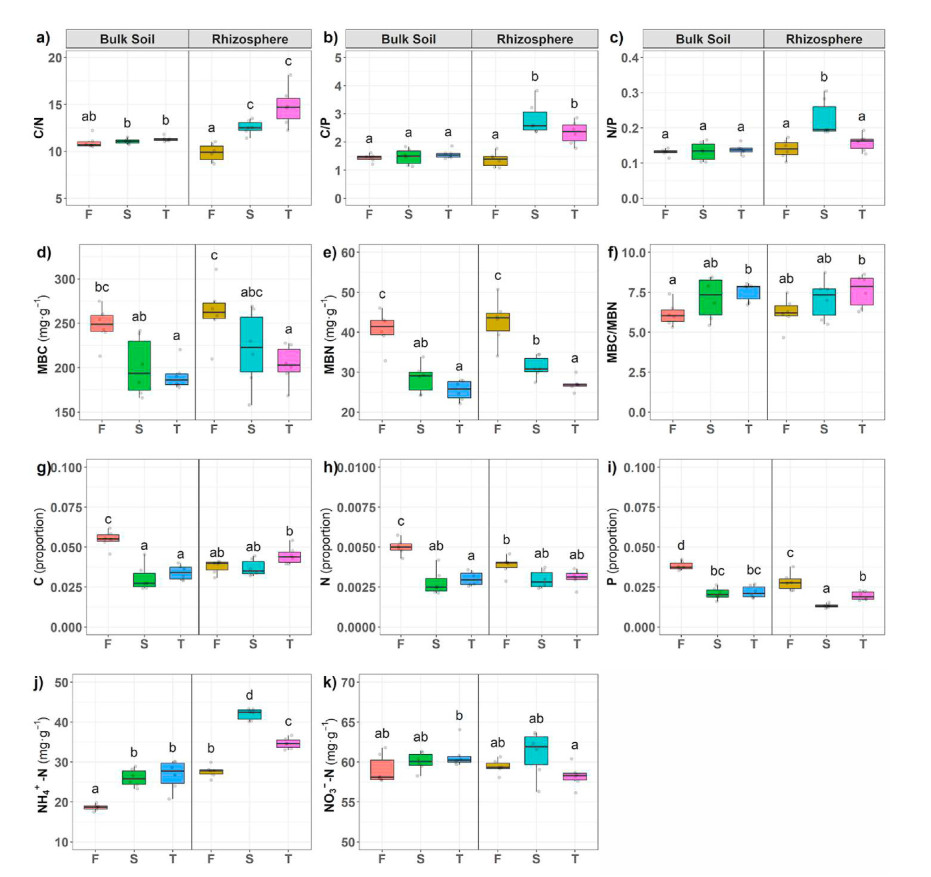

Bulk soil and rhizosphere soil properties of seedlings and coppice plantations were significantly different (Fig. 1). NO3−-N is the main form of available soil N in BL plantations, ranging from 59.28% to 76.01%. We found that TN, MBN, and MBC in both bulk soil and rhizosphere soil were significantly higher in seedlings plantations than coppice plantations (23.32%–80.24% and 18.71%–58.30%, respectively).

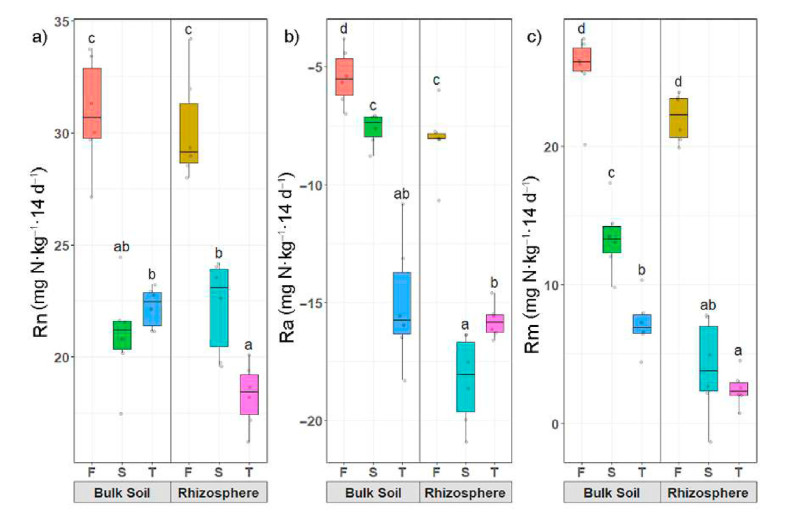

The bulk soil and rhizosphere nitrification (Rn), ammonification (Ra), and net N mineralization (Rm) were significantly higher in seedling plantations than in coppice plantations (Fig. 2). In addition, we found that the Rn and Rm were positive, while the Ra was negative. For example, in bulk soil of F, Rn, Ra, and Rm of seedling plantations were 30.89, −5.45 and 25.44 mg N·kg−1·14 d−1. Rn, Ra, and Rm in the rhizosphere were 30.16, −8.10 and 22.05 mg N·kg−1·14 d−1, respectively. Conversion from seedling to coppice plantations resulted in decreases of 31.98%, 40.18%, 47.44% in bulk soil, and 25.00%, 130.12%, 81.95% in the rhizosphere, respectively.

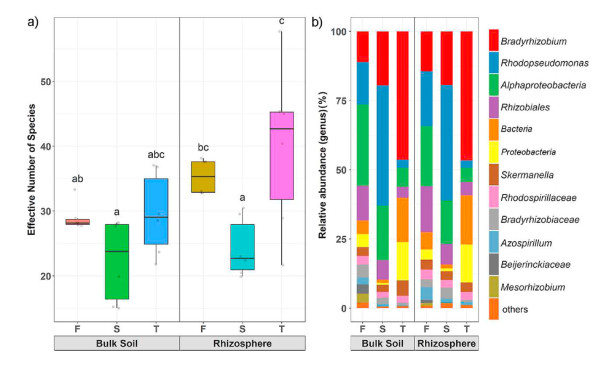

The Hill diversity indices of soil diazotrophs ranged from 22.35 to 39.84 and were significantly different between the seedling and coppice plantations (Fig. 3a). The diazotrophs Hill diversity indices in the seedling plantations were 29.02 and 35.34, significantly higher than those in the coppice plantations (p < 0.05, S (22.35 and 24.30), T (29.56 and 39.84), respectively) for bulk soil and rhizosphere.

The relative abundance of the soil diazotrophs at the genus level based on the nifH gene is displayed in Figs. 3b and 4. There were significant differences in soil diazotrophic communities between seedling and coppice plantations for bulk soil and rhizosphere soil (PERMANOVA, bulk soil, p = 0.001, Rhizosphere, p = 0.001). Overall, the BL soil diazotrophic communities in the seedling plantations were dominated by Proteobacteria at the phylum level (Fig. S1), unclassified-c-Alphaproteobacteria (22.37% and 29.28%), unclassified-o-Rhizobiales (15.40% and 13.31%), and Bradyrhizobium (12.00% and 11.74%) for rhizosphere and bulk soil at the genus level (Fig. 3b), respectively. However, in the first-generation coppice plantations (S), the dominant genus was Rhodopseudomonas (43.56% and 41.84%), followed by Bradyrhizobium (17.47% and 22.72%). In the second-generation coppice plantations (T), the dominant genus was Bradyrhizobium (45.95% and 47.86%), followed by unclassified-k-norank-d-Bacteria (16.40% and 14.92%) for rhizosphere and bulk soil at the genus level, respectively. The relative abundances of Rhodopseudomonas and Bradyrhizobium were close to half of the total in coppice plantations (Fig. 3, Fig. S2), suggesting an increasingly homogenized composition of diazotrophic communities.

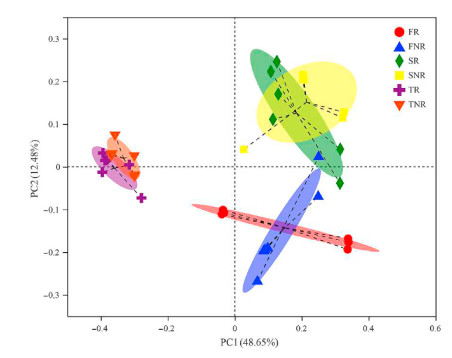

We used Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) to evaluate the similarity of diazotrophic communities in bulk soil and rhizosphere. The PCoA plot (Fig. 4) exhibited the Bray-Curtis distance for nitrogen-fixing microorganism communities found in seedling and coppice plantations for bulk soil and rhizosphere. In bulk soil, the distribution of the nitrogen-fixing microorganism communities in the seedling plantations was clearly separated from coppice plantations; the same results appeared in rhizosphere soil. Based on Adonis tests, a significant difference was observed between the BL seedling and coppice plantations, bulk soil (R2 = 0.586, p < 0.001), and rhizosphere (R2 = 0.625, p < 0.001).

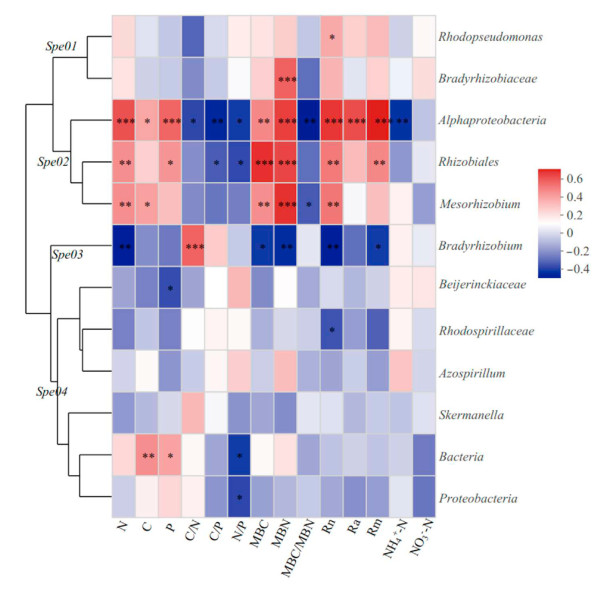

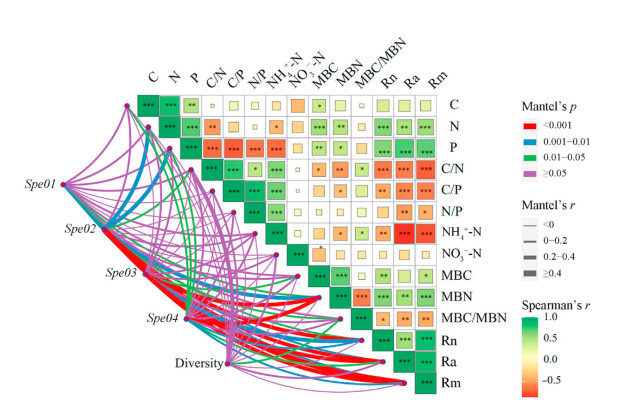

Based on the composition and abundance of OTUs, the dominant diazotrophic communities are clustered into four categories (Fig. 5). Spe01 includes Rhodopseudomonas and Bradyrhizobiaceae; Spe02 includes Alphaproteobacteria, Rhizobiales, and Mesorhizobium; Spe03 includes Bradyrhizobium; and Spe04 include Beijerinckiaceae, Rhodospirillaceae, Azospirillum, Skermanella, unclassified-k-norank-d-Bacteria, and unclassified-p-Proteobacteria. Spe02 and Spe03 are significantly correlated with soil properties (Fig. 6). Notably, Spe02 consists of only the Bradyrhizobium community, a special group in the nitrogen-fixing bacteria community of Robinia pseudoacacia.

The Spearman rank-order correlation was used to evaluate the relationships between soil properties and the diazotrophic communities (Fig. 6). N mineralization was closely correlated with soil properties. Nitrogen had a positive correlation with Rn (r = 0.78, p < 0.01) and Rm (r = 0.77, p < 0.01), but negative correlation with Ra (r = −0.59, p < 0.01). Ra was positively correlated with C/N (r = 0.48, p < 0.01) and N/P (r = 0.50, p < 0.01). The soil properties exhibited a significant correlation with Mesorhizonium, f_Beijerinchiaceae, o_Rhizobiales, c_Alphaproteobacteria, and Bradyrhizobium. c_Alphaproteobacteria was significantly and positively correlated with MBN, Rn, Ra and Rm (r = 0.713, p < 0.001; r = 0.636, p < 0.001; r = 0.70, p < 0.001; r = 0.77, p < 0.001, respectively). Bradyrhizobium was significantly and negatively correlated with MBN, Rn, Ra and Rm (r = −0.592, p < 0.001; r = −0.524, p < 0.01; r = −0.455, p < 0.01; r = −0.566, p < 0.001, respectively).

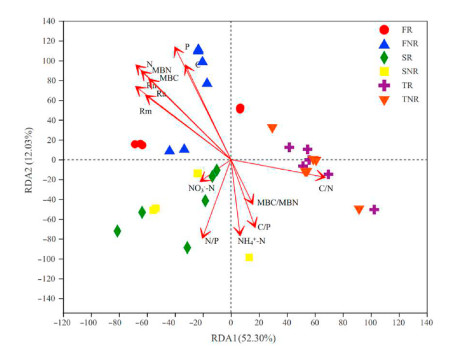

Thirteen variables were selected to perform RDA on diazotrophic community composition. The RDA analysis for the soil attributes explained 64.33% of the data variability in the first two axes (Fig. 7). There were obvious differences in type and quantity of factors affecting community compositions among samples. For FR and FNR samples, diazotrophic communities were closely related to C, P, N, MBN, MBC, Rn, Ra, and Rm. In terms of SR and SNR samples, four factors affected the diazotrophic structures including NO3−-N, N/P, NH4+-N, C/P and MBC/MBN. However, only C/N factor has an influence on the communities of TR and TNR samples (Fig. 7). The Mantel test analysis showed that Rn, Ra, Rm, and MBN were the important factors in shaping the diazotrophic communities (Table 1). In addition, the results of random forest analysis also showed that Rn, Ra, Rm, and MBN were the most important environmental variables linked to changes in diazotrophic community composition (Fig. S3).

| Variables | R | p |

| Rm | 0.359 | 0.001 |

| Ra | 0.307 | 0.001 |

| Rn | 0.281 | 0.001 |

| MBN | 0.274 | 0.001 |

| N | 0.194 | 0.002 |

| P | 0.188 | 0.003 |

| MBC | 0.193 | 0.004 |

| C/N | 0.100 | 0.062 |

| NH4+-N | 0.068 | 0.102 |

| C | 0.068 | 0.108 |

| MBC/MBN | 0.031 | 0.230 |

| NO3−-N | −0.025 | 0.645 |

| C/P | −0.051 | 0.803 |

| N/P | −0.069 | 0.858 |

Black locust is an ideal tree species for short-rotation biomass production with many advantages such as rapid growth, high drought tolerance, and nitrogen-fixation, as well as the ability to reproduce via stump shoots in response to harvest (Carl et al., 2019). Nevertheless, the multi-generation coppice plantations on Mount Tai negatively impacted soil quality (Li et al., 2021). Our study supports previous observations of the adverse effects of forest conversion on soil properties, soil microbial communities, and enzyme activities (Wang et al., 2017; Cai et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2018). Additionally, our results revealed that the plantation conversion from seedling to coppice stands significantly decreased the concentration of soil N, P, MBC, and MBN, while increased soil NH4+-N and C/N concentrations (Fig. 1). There were no significant differences in other soil variables, indicating that the impact of forest conversion on soil nutrients is inconsistent, partly in line with the results of Li et al. (2021). These outcomes may be associated with complex nutrient pools in forest ecosystems (Yang et al., 2018) and negative ammonification (Fig. 2).

Forest conversion has a specific effect on soil C and N transformations (Yang et al., 2018). Our results showed that plantation conversion increased the rhizosphere carbon and decreased bulk soil carbon by including N-fixers that improved the soil C, but the response may be site- and species-specific (Hoogmoed et al., 2014). As a light-demanding tree species, black locust growth is limited if the light availability is weak (Carl et al., 2019). In BL coppice plantations, the density of black locust regeneration is higher. Due to the already-established root systems, BL grows faster and obtains energy from light. Subsequently, the microbial community may require higher amounts of rhizosphere C for their energy consumption that in turn fixes more gaseous N2. An earlier study found that the N content in plantations' soils decreased remarkably following the conversion from natural forests (Xu et al., 2010), and our results support this finding (Fig. 1). In BL plantations, soil nitrogen input primarily comes from the decomposition of plant detrital input and roots and biological nitrogen fixation (Yang et al., 2011). The outputs are the harvesting and removal of the plant (a loss from the ecosystem) and nitrogen leaching to groundwater or emission to the atmosphere (Li et al., 2012). BL coppice plantations have lower net mineralization and decreased nitrogen inputs, further decreasing soil nitrogen.

Phosphorus is an essential nutrient for BL trees (Carl et al., 2018), which could affect the nitrogen fixation of plants (Augusto et al., 2013). Our results suggest that the decrease in soil P was caused by plantation conversion, which was in accord with carbon and nitrogen reduction (Li et al., 2021). The same trend also appeared in MBN and MBC, which are considered indicators of soil quality and as a measure of N availability for plants due to their sensitivity to soil disturbance by land-use changes and tillage activities (Yang et al., 2010). MBC and MBN provide the basis for the survival of soil microbes (Vitali et al., 2016; Moghimian et al., 2017). Additionally, our results showed that MBN and MBC were negatively correlated with soil C/N ratio and positively with total N, results which were in line with the findings of Moghimian et al. (2017) and Hoogmoed et al. (2014). The C/N ratio can be a critical indicator for determining biological processes. Earlier work has shown that soil C/N ratio decreased after planting black locust (Cao et al., 2017). By contrast, our results revealed soil C/N ratio increased in coppice plantations due to lower soil nitrogen content. Lower soil C/N will reduce the turnover and retention of soil nutrients (Ng et al., 2014).

Net N mineralization rate and mineral N content in seedling plantations were significantly higher in coppice plantations (Fig. 2), and Rn and Rm were positive, while Ra was negative. The results suggest that soil net nitrogen mineralization decreased in coppice plantations. Our results demonstrated that nitrification exceeded the net mineralization, consistent with earlier observations (Wei et al., 2011; Kong et al., 2019). Typically, soil microorganisms are C limited, and it has been shown that increased N can depress total microbial biomass. Generally, net soil N mineralization rate decreases with a decrease in root biomass (Wang et al., 2018a) due to the immobilization of inorganic N to satisfy the microbial N demand. Furthermore, a lower soil C/N ratio accelerates the activities of microorganisms (Usman et al., 2000; Wei et al., 2011), which would explain our experimental results. In seedlings plantations, the C/N ratio was lower than that of coppice plantations. We found that NH4+-N content in coppice plantations was higher than that in seedling plantations, and the higher NH4+-N level in the soil might inhibit soil N mineralization rate (Geisseler et al., 2010).

As microbial communities drive soil net nitrogen mineralization, the reductions in soil microbial biomass carbon (MBC) were positively related to N mineralization rates (Geisseler et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2021). Our results showed that the MBC was lower in coppice plantations (Table 1), which can increase the efficiency of soil N mineralization (Li et al., 2020). Still, we found lower N mineralization in coppice plantations, suggesting that the N cycle was limited. N mineralization of soil depends strongly on the substrate contents, including total N, soil organic C, water-soluble N, and dissolved organic C (Zhang et al., 2016). Our results also showed that the Rn and Rm had positive correlations with soil C, N, and P, consistent with Booth et al. (2005). Therefore, it might be that the BL coppice plantation grows faster, requiring a large amount of nutrients, and the uptake of mineral N by roots may result in decreased mineral N (Kong et al., 2019).

The diazotrophic microorganisms are primary drivers of soil BNF that may be significantly correlated with the communities' attributes, including abundance, composition, and activity (Reed et al., 2011; Pogoreutz et al., 2017). Our results show that diazotrophic community composition was significantly altered by the coppice plantations. In our study, the Proteobacteria phylum was the most dominant diazotrophic group (Fig. S1), generally similar to results from other studies (Wang et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2019a). However, the diazotrophic communities' structures at the genus level were significantly different in seedling and coppice plantations (Figs. 3‒5 and Fig. S2). Our results suggest that forest conversion-induced variation in diazotrophic β-diversity and reduced α-diversity (Hill index) is consistent with Peerawat et al. (2018). At the genus level, the diazotrophic communities in coppice plantations commonly transition to Rhodopseudomonas or Bradyrhizobium-dominated communities (Fig. 3 and Fig. S2), but in seedling plantations, there were higher relative abundances of several diazotrophic genera, including Rhodopseudomonas, Bradyrhizobium, o_Rhizobiales, and c_Alphaproteobacteria, which could favor distinct subsets of diazotrophic communities, suggesting that there is a tendency of simplification of diazotrophs in coppice plantations. The change in beta diversity in response to forest conversion is an indication of biotic homogenization, and the process by which the similarity of communities increases over time and/or space (Rodrigues et al., 2013). In our results, the increasing similarity in the beta diversity of coppice plantations (Fig. S4) shows the soil diazotrophic homogenization in coppice plantations. The homogeneity of this characteristic will change the function of the ecosystem and reduce the ecosystem's ability to recover from disturbances.

Generally, BNF is carried out by the Rhizobia in the anaerobic environment of the nodule. The Rhizobiales are well known for forming root nodules with legumes and conducting symbiotic nitrogen-fixation (Schmidt et al., 2017). In our results, the relative abundance of Rhizobiales in seedling plantations was higher than that in coppice plantations, which indicated it had more root nodules and, to some extent, it had a stronger BNF ability. Therefore, it would produce more ammonium. Because of the lower nitrification in coppice plantations, the rate of ammonium transferring to nitrate decreased, which would lead to the accumulation of ammonium (Fig. 1). It has also shown that increased available soil N inhibits colonization by Rhizobia. If the plant demands for N are being met by available soil N, then the need for the symbiotic relationship with Rhizobia is no longer advantageous to the plant.

Soil nutrient content has been recognized as a key determinant for soil microorganism survival and species compositions (Kerfahi et al., 2016; Meng et al., 2017; Wood et al., 2017). The composition and abundance of the diazotrophic communities in soil may be correlated with several environmental factors and vegetation types (Rodríguez-Blanco et al., 2015; Saleem et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2019a). In our study, the soil nutrient (N and P) was significantly correlated with the diazotrophs. Mantel test results showed that the diazotrophic community presence was explained mainly by nitrogen mineralization, MBN, MBC, N, and P (Table 1). Nitrogen mineralization was the most significant contributor to diazotrophs in measured variables. Previous studies have shown that soil N and MBC drive diazotrophic community structure dominance (Chen et al., 2019a; Zhao et al., 2021). Our results showed that the soil nitrogen had a significantly positive correlation with diazotrophic community structures, consistent with the results of Che et al. (2018). In our study, coppice plantations had higher levels of inorganic nitrogen (NH4+-N and NO3−-N), which may reduce the activity of diazotrophs (DeLuca et al., 1996; Xu et al., 2019) and reduce nifH gene expression (Mirza et al., 2014), and finally lower the BNF (Chen et al., 2019b). Along with the growth of BL, more rRNA is needed to increase the protein synthesis, which leads to an increase in the N content of leaves (Xu et al., 2019). Our results showed that coppice plantations had a lower P and higher N/P ratio, further inhibiting the BNF. The reason was that phosphorus is one of the critical factors limiting nitrogen fixation due to the high adenosine triphosphate (ATP) demand of BNF (Bell et al., 2014) and P deficiency-induced more restrictive effects on diazotrophic communities (Tang et al., 2017).

Bradyrhizobium is a common slow-growing bacterium (Koponen et al., 2003), which plays an essential role in the nitrogen cycle in forest ecosystems (Meng et al., 2017). However, Bradyrhizobium can only fix N and increase N input after inoculating legume plants (Liu et al., 2019). We found that the relative abundance of Bradyrhizobium in coppice plantations was higher than that in seedling plantations (Figs. 3 and 4, and Fig. S2), which suggests that coppice could increase its abundance. The explanation may be that the low nitrogen content and higher C/N in the soil of the coppice plantations stimulated the increase in the activity of nitrogen-fixing microorganisms (Nie et al., 2021). Studies have found that Bradyrhizobium has a pronounced capacity for N2 fixation (Straub et al., 2004; Sánchez et al., 2011). However, its nitrogen fixation function is not sufficient to meet the growth needs of coppice plantations. In addition, we found that the relative abundance of Bradyrhizobium was negatively correlated with N, MBN, MBC, Rn and Rm (Fig. 5), which was consistent with the results of Hu et al. (2018). Therefore, it may be that N inhibits the activity of Bradyrhizobium (Xu et al., 2019), and soil nutrient availability was the most dominant factor in shaping diazotrophic community structure (Wang et al., 2017).

Our results suggest the conversion of black locust plantations impacts nifH microorganism communities, N mineralization, microbial biomass N, and soil properties. We found that the dominant species changed from Rhodopseudomonas, Bradyrhizobium, o_Rhizobiales, and c_Alphaproteobacteria in seedling plantations to Bradyrhizobium and Rhodopseudomonas in coppice plantations. This outcome suggests that the coppice stand can normalize diazotrophic soil communities, which in turn affects the function of diazotrophic communities.

As the forest converted to different plantation types, the tendency of dominant species varied. Rm, Rn, and MBN were the most sensitive factors to diazotrophic microorganisms. Converting seedling plantation to a coppice plantation decreased the soil MBN, MBC, Rn, Rm, N, and P, but significantly increased the concentration of NH4+-N, demonstrating that plantation conversion had a positive impact on inorganic N, while the effects on soil mineralization and nifH were negative. NH4+-N produced by biological nitrogen fixation is more synthesized into organic nitrogen. Therefore, to increase the nitrogen fixation and nitrogen use efficiency of black locust, reducing the proportion of the multi-generation coppice plantations in this region is advisable.

KL and HMT conceived and designed the experiment; RQN and KL analyzed the data; HMT and WXS obtained the data in the field; KL and CRL wrote the first draft of the paper and WKM, STO and LSB contributed to the writing and data analysis. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

We are very grateful to all the students who assisted with data collection and the experiments. We also thank three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions on this paper.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fecs.2022.100025.

| Variables | R | p |

| Rm | 0.359 | 0.001 |

| Ra | 0.307 | 0.001 |

| Rn | 0.281 | 0.001 |

| MBN | 0.274 | 0.001 |

| N | 0.194 | 0.002 |

| P | 0.188 | 0.003 |

| MBC | 0.193 | 0.004 |

| C/N | 0.100 | 0.062 |

| NH4+-N | 0.068 | 0.102 |

| C | 0.068 | 0.108 |

| MBC/MBN | 0.031 | 0.230 |

| NO3−-N | −0.025 | 0.645 |

| C/P | −0.051 | 0.803 |

| N/P | −0.069 | 0.858 |